Table of Contents

Schema Theory

General

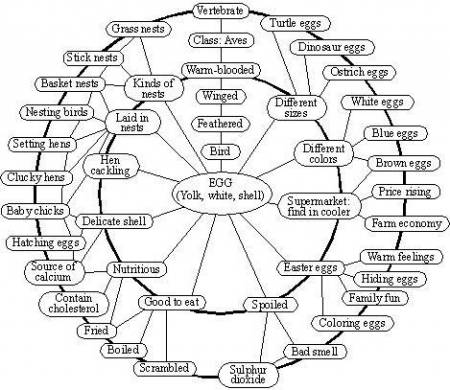

Concept of schema theory, one of the cognitivist learning theories, was firstly introduced in 1932 through the work of British psychologist Sir Frederic Bartlett1) (some suggest it was first introduced in 1926 by Jean Piaget2)) and was further developed mostly in 1970s by American educational psychologist Richard Anderson3). Schema theory describes how knowledge is acquired, processed and organized. The starting assumption of this theory is that “very act of comprehension involves one’s knowledge of the world”4). According to this theory, knowledge is a network of mental frames or cognitive constructs called schema (pl. schemata). Schemata organize knowledge stored in the long-term memory.

What is schema theory?

The term schema is nowadays often used even outside cognitive psychology and refers to a mental framework humans use to represent and organize remembered information. Schemata (“the building blocks of cognition”5)) present our personal simplified view over reality derived from our experience and prior knowledge, they enable us to recall, modify our behavior, concentrate attention on key information6), or try to predict most likely outcomes of events. According to David Rumelhart7),

- “schemata can represent knowledge at all levels - from ideologies and cultural truths to knowledge about the meaning of a particular word, to knowledge about what patterns of excitations are associated with what letters of the alphabet. We have schemata to represent all levels of our experience, at all levels of abstraction. Finally, our schemata are our knowledge. All of our generic knowledge is embedded in schemata.”

Schemata also expand and change in time, due to acquisition of new information, but deeply installed schemata are inert and slow in changing. This could provide an explanation to why some people live with incorrect or inconsistent beliefs rather then changing them. When new information is retrieved, if possible, it will be assimilated into existing schema(ta) or related schema(ta) will be changed (accommodated) in order to integrate the new information. For example: during schooling process a child learns about mammals and develops corresponding schema. When a child hears that a porpoise is a mammal as well, it first tries to fit it into the mammals schema: it's warm-blooded, air-breathing, is born with hair and gives live birth. Yet it lives in water unlike most mammals and so the mammals schema has to be accommodated to fit in the new information.

Schema theory was partly influenced by unsuccessful attempts in the area of artificial intelligence. Teaching a computer to read natural text or display other human-like behavior was rather unsuccessful since it has shown that it is impossible without quite an amount of information that was not directly included, but was inherently present in humans. Research has shown that this inherent information stored in form of schemata, for example:

- content schema - prior knowledge about the topic of the text

- formal schema - awareness of the structure of the text, and

- language schema - knowledge of the vocabulary and relationships of the words in text

can cause easier or more difficult text comprehension8), depending on how developed the mentioned schemata are, and weather they are successfully activated.9). According to Brown10), when reading a text, it alone does not carry the meaning a reader attributes to it. The meaning is formed by the information and cultural and emotional context the reader brings through his schemata more than by the text itself. Text comprehension and retention therefore depend mostly on the schemata the reader possesses, among which the content schema should be one of most important, as suggested by Al-Issa11).

What is the practical meaning of schema theory?

Schema theory emphasizes importance of general knowledge and concepts that will help forming schemata. In educational process the task of teachers would be to help learners to develop new schemata and establish connections between them. Also, due to the importance of prior knowledge, teachers should make sure that students have it.

“The schemata a person already possesses are a principal determiner of what will be learned from a new text.”12)

Schema theory has been applied in various areas like:

- reading comprehension - schema theory is often used to assist second language learning since it often contains reading a lot of texts in the target language. Failure to activate adequate schema when reading a text has shown to result in bad comprehension15). Various methods have been proposed for dealing with this issue16) including giving students texts in their first language on certain topic about which they will later read in target language.

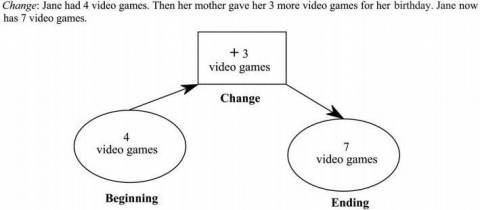

- mathematical problem solving - Jitendra et al.17) conducted a research showing that 3rd-graders taught to using schemata to solve mathematical problems formulated in words performed better than their peers who were taught to solve them in four steps (read and understand/plan to solve/solve/look back and check).

Criticisms

Explanations of structures of knowledge have been criticized for being rather unclear about what exactly can count as a schema and what does a schema include. The idea of schemata as more complex constructs of memory has also been questioned. Some researchers18) suggest schemata as such are just networks of interacting simple (low-level) units activated at the same time. For example, a classroom schema is formed by simultaneously activated units of a blackboard, desks, chairs and a teacher.

On the other hand, schema theory was the starting point or a component for many other cognitivist theories and theorists like Jean Mandler19), David Rumelhart (modes of learning) or Marvin Minsky (frame theory) who have further expanded it's concepts, and was also included in works of many other theorists like Sweller's (cognitive load theory) or Ausubell's (assimilation theory).

Keywords and most important names

- schema theory, schema, schemata, schema theory of discrete motor learning

Bibliography

Schema theory of learning. LinguaLinks Library, 1999. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

Schema theory of learning. The Encyclopedia of Educational Technology. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

Routledge Encyclopedia of Language Teaching and Learning. Schema and script theory. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

Qualitative Research Methods. Schema Theory (drawn from D’Andrade 1995). Retrieved March 15, 2011.

Wiki: Schema Theory. Retrieved March 15, 2011.